On December 23rd our co-founder Nur Güzeldere and I took part in a project from film studies that included filmmaking. Each group had two poems to base their film on, one of them being a poem by Gonca Özmen and the other a poem by Matthias Göritz, who was with us during the project, thanks to Gonca Özmen. During the meeting, we, students spent time with him where we discussed poetry and film.

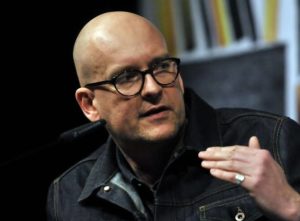

During all this, Nur and I had another thing in our minds: We had to include him on 9 Magazine! So we decided to interview him since we thought it would be the best way to portray Matthias Göritz as an artist. Here is our interview:

How would you describe your life with and without poetry?

I think more or less my life as a person or as an admirer of poetry and literature is from the very first beginning. When I was little my father and my mother were telling stories and my grandmother was reading from “1001 Nights“. My father was reciting the old stories of The Odyssey and The Iliad because he was a very poor man when he grew up, he had only the books, which was propelling him to something big and so he wanted to give this to me as well and it resonated with me. I remember one of my first memories is that I was sitting on the lawn mower and he was reciting the stories of Achilles and the love stories of bygone times. I think in my head, I started to write poetry or tell stories even before I could write and read myself. So, from the very beginning when I was starting to read I was also starting to write and invent stories. There’s no real life without poetry for me, so I can’t even imagine how that might be.

How do you think poetry adds to the interpretation of a film?

I think the visual language and the actual poem in the poetical language have something in common, if you want to talk about poetry being a little bit opposed to simple narration. A poem is something like a hybrid, it is a space, like a picture is a space, and it is also moving forward towards an end from the beginning. The end is creating images, a fragment of narration, something which the reader or the viewer has to look on in a more close fashion or even a more open fashion. So it’s a moving picture and this is the definition of film, it’s a moving picture. So it’s also a hybrid of one frame which has to be stylized beautifully, which is also a little bit disruptive because you always have this interest where you think “Oh my God what am I looking at? What is it creating as a feeling? What is the soundtrack like? What do I really think?” Then you are in the next picture and its kind of like the passion of a good poem. They both inspired each other. Films inspired poetry tremendously but I think poetry inspired film even more and especially experimental films because experimental films are much more like poems and much less like novels or short stories and the narrative way of filmmaking. The ninety minutes of filmmaking, which are based on clear character development, clear conflicts and the solution at the end, we already had that now for more than a hundred and twenty years. It is a little bit boring. I think the future of movie making also lies in this more poetical way of using frames, language, songs, and sounds, manipulating the inner world of its viewers. Music videos did that for a long time and I think now the most exciting thing for me is to explore what poetry and movies can be when they are coming together. Can they really attract a new audience for the poems and can they also attract a new audience for the visual arts? Maybe there’s even a possibility of influencing the narrative forms of cinema. There can be an exchange for young filmmakers to become a little bit more disruptive and a little bit more daring with plots, with characters. I hope that the art of cinema will never die out but it will renew itself, and I think poetry is the key to that.

Where do you get your inspirations from?

That’s a very hard question. Well, you never know when the inspiration is hitting you but I definitely get it from living here in Istanbul. In 2015 I got this grant, which allowed me to come over and stay here for five years and for five months and I came back every year for a couple of months because I was struck, not so much by inspiration but by a story that I wanted to do research on and explore more deeply. The new novel I am writing is about the 1930s here in Turkey, the time of the reform of the Turkish language and the German immigration, which was really prominent, in Istanbul. Since 1935 a lot of German architects, philosophers, linguists, writers were invited to be part of the reform at the universities. In Istanbul University, for example, you had the most famous writer and literary critic of the world at that time, Erich Auerbach, a German Jew who fled Nazism in Germany like thousands of other German Jews and German leftist immigrants who found a new home in Turkey, and closely collaborated with Turkish intellectuals to construct a new Turkey. That was very interesting for me and that inspiration never left me and is also connected with a passion for a place and Istanbul is that place. What fascinates me about Istanbul is that, like the hero of my book, you can never become a Turk if you are not born a Turk but you can belong to the city of Istanbul. Istanbul is like New York or Venice, it’s a place so big that it allows you to feel yourself in a world that has a lot of layers and differences, which still welcomes you and allows you to explore who you are and do something that you feel building a world together.

How is German literature different than Turkish literature?

Well, that is quite a big question. Even though I’ve lived in Turkey since 2015 I am really not qualified to completely answer that question. I can maybe say in Turkey there is more lyrical poetry, poems based on feelings, images connected with those feelings. In that sense, German poetry is more driven to hybridity, concepts, and play of language within the language. I know that is also changing a lot in the Turkish context and we also have poets influenced by John Ashbery or language poetry from the States or from Germany like Nilay Özer, and poets such as Efe Duyan, who are more drawn to the social sphere of poetry, coming from a tradition of Nazım Hikmet but also from Bertolt Brecht, who is very prominent here in Turkey. The social sphere is probably not as prominent in Germany. For novels, I would say one of your novel writers, Orhan Pamuk, had a great influence on the German sphere because people were really enjoying his very broad novels about Turkey. That definitely hit the spot because we also have this tradition of family novels, which are also social novels, from Thomas Mann. I would say this is very similar. Besides from that I need many more years as a reader of Turkish literature and I can only read it in translation so far, so it depends on what is translated. The exchange between Germans and Turks in the field of literature is going to be very exciting for the next years, to discuss and comment on each others’ literature.

How have the places you lived in inspired your view on your experiences?

I think one of the most important times in my life it was 1994. I was really tired and I faced a lot of tragedies in my own life. I decided that I needed a break and I took all the money I still had and went to Russia because I was falling in love with a Russian poet from the 19th century, his name was Mikhail Lermontov. He was the rival and successor of Pushkin and died very young, wrote beautiful dark poetry and I wanted to translate his poetry and in order to do that I felt like I had to go to Russia, take the time out learn the language and start honestly to translate him. Moscow was a very interesting place at that time, very open and changing a lot but I didn’t even know what this thing would be called in Russian. So this distance of a world which is there and the language I was able to express this world in was huge. I think that really had an influence on my poetry. I wrote a lot of poems at that time, I was really lucky, those poems won a really big German poetry price, and I think that was kind of like the beginning of my career, not because I won this price, which also made it easier for me afterward to publish and to be successful as a poet and then later as a novelist, but because it is the essence of what my writing is. It is the discovery of a place, a language, the experience of something new and the recreation of all those feelings and all those insights in a poem.

…

…

We really enjoyed our time with Matthias Göritz. Thank you Matthias Göritz and Gonca Özmen, who made this project and our interview possible!