Which artists cross our minds first when we think about it? Van Gogh with his cut ear, Dali with his unusual surreal artworks, maybe Frida Kahlo with her unibrow or Monet with his water lilies.

The list could, of course, go on, but what I’m trying to say is: Western art and predominant European names come to mind. Over the centuries, Western art, in the history of art as well, has been extensively told and taught.

So what exactly do we know about East Asia, Japanese art especially?

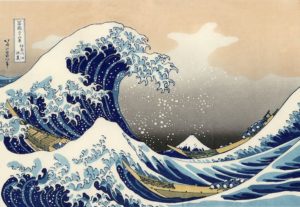

Frankly, I think of Hokusai’s “The Great Wave off Kanagawa” first. (Also known as The Great Wave or The Wave).

Since I learned that the painting belongs to Hokusai just last month, it’s obvious I don’t know much about Japenese art.

Seeing I received so many positive reviews and feedback from many people about the forgotten series of women artists in the history of art, I decided to expand this series. So far, along with the women artists I’ve chosen from France, Russia and Turkey, now one of the most important women of Japanese art is added: Uemura Shoen.

Uemura Shoen was born in Kyoto in 1875 under the name of “Tsune Uemura”. Because her father died two months before her birth, Shoen made sure that her bond with her mother was strong and lasting throughout her life. Uemura wasn’t born into a rich and powerful family, her mother ran a tea shop in Kyoto. Shoen spent her childhood at the corner of the tea shop drawing while waiting for her mother.

Born gifted Shoen’s drawings started attracting attention in her mother’s tea shop when she was just a little girl. This led to Shoen getting painting lessons at the age of 12. But then she dropped out of school and left her education undone.

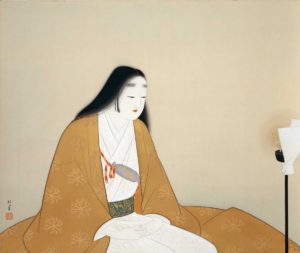

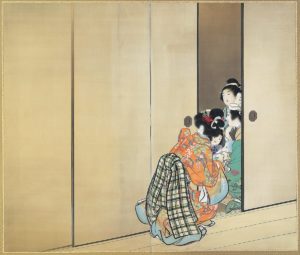

Uemura Shoen started working as Suzuki Shonen’s assistant after her school years. She began painting in bijin-ga style at Suzuki Shonen’s workshop. Bijin-ga is translated as portraits, pictures and prints of beautiful women. Throughout her life, Shoen kept painting in the style of bijin-ga from her own perspective, the way she learned back in the workshop. Because of the respect she had towards her teacher Shonen, Uemura changed her last name into Shoen.

When Uemura was only fifteen, her paintings were sold to the Duke of Connaught and Arthur, Prince of Wales. Her paintings spread from Japan to the whole world, and she won awards in different countries. The period she lived in, at the beginning of the twentieth century, the oil paints from the Western influence in Japan were popular, while Shoen iwaenogu (mineral pigment) and Japanese history and tales were embraced.

The bijin-ga style in which Shoen depicts beautiful women goes back to the 17th century in the history of Japenese art. During the Edo (1603-1868) period, bijin-ga, which comes out with the style that focuses on ordinary people, referred to as Ukiyo-e and nature portrayed women as underclass/lower-class citizen, while men were upper class. During the Taisho era which Shoen lived in, bijin-ga depicted women equal to men and without discrimination (steps were taken on inequality).

Shoen had a hard time in her 40s after losing her mother and spouse. After the loss of her mother, Shoen began to add more mother-child relations and her own childhood memories in her artwork.

Uemura Shoen was the first living woman to receive the “Order of Culture” award in 1948. Just a year later, she died of cancer in 1949.

Shoen may seem to have only painted beautiful women, but she’s portrayed her own life and thoughts in a patriarchal society, drawing women from everyday life as elegant as a queen. Even though she never referred to herself as a feminist, she moved to art history by living and reflecting it in her paintings.

…

Translated by Yağmur Özkardeş

…